Cuba and America, Victim and Perpetrator in I Am Cuba

Summary:

The vignette of Enrique criticizes American imperialism by exposing its cultural, military, and economic dominance, highlighting Cuba's subjugation under capitalist oppression. Through symbolic framing of characters and environments, the film portrays the United States as a detestable antagonist and the pre-communist Cuban government as an accomplice in its exploitation of Cuba. This is consistent with the film's overall anti-American sentiment, as it sought to justify the Cuban Revolution as a necessary rebellion against foreign control.

Notes:

This is a looong essay. I remember I stayed up late multiple nights to write this. Really happy with how it turned out.

Given the geographical proximity, it is unsurprising that the United States has played a major role in the trajectory of Cuban history. After Fulgencio Batistaʼs military coup, his regime prioritized American business interests at the expense of the Cuban people, essentially selling out the nation in exchange for U.S. support and turning it into a profit center for American corporations (Savela). In response, there came revolutionaries who sought to free Cuba from foreign control and reclaim national sovereignty. Following Batistaʼs ousting, the Cuban-Soviet co-production propaganda film I Am Cuba (1964) was produced, featuring four vignettes that explore the life of Cuban people at the dawn of the Cuban Revolution. The vignette of Enrique criticizes American imperialism by exposing its cultural, military, and economic dominance, highlighting Cubaʼs subjugation under capitalist oppression. Through symbolic framing of characters and environments, the film portrays the United States as a detestable antagonist and the pre-communist Cuban government as an accomplice in its exploitation of Cuba. This is consistent with the filmʼs overall anti-American sentiment, as it sought to justify the Cuban Revolution as a necessary rebellion against foreign control.

The vignette opens with Enrique and his fellow student revolutionaries bombing a drive-in theater, setting it ablaze in a symbolic act of defiance against the Batista regime and American cultural imperialism. The theater was screening a propaganda film that glorified Batistaʼs rule, featuring real-life footage of Cuban elites wearing suits and indulging in luxury, which is reflective of the regimeʼs corruption (see Fig. 1).1 Film scholar Lida Oukaderova describes the studentsʼ action as “an act of cinematic revolt,” uniting the moviegoers with the revolutionaries. As such, the bombing can be understood as a direct rebellion against the Batista government and Western influence in Cuba.2 A not-so-subtle way of calling for the death of a dictator, if you will. The setting is significant: the drive-in theater is a uniquely American concept and its usage in this scene represents Cubaʼs assimilation into capitalist modernity. Oukaderova points out that the viewers are “sealed” in endless rows of motionless cars, away from each other and from reality. This renders them passive consumers of propaganda and capitalism—bourgeois who are blinded by deception and content in their subjugation. This static staging is destabilized by the chaotic bombing, challenging complacency of American cultural imperialism and capitalist dominance.

As seen in Figure 2, the screen is set ablaze by Enrique and his comrades. As they flee the scene, the camera movement reframes to center the flames, lingering on them for about thirty seconds. The prolonged focus on the fire makes the destruction the focal point and amplifies a threatening message: “Burn it down—all of it!” The fire evokes imagery of death and rebirth; the destruction of the old order paving the way for a new and revolutionary Cuba that will rise from the ashes and free from foreign control.

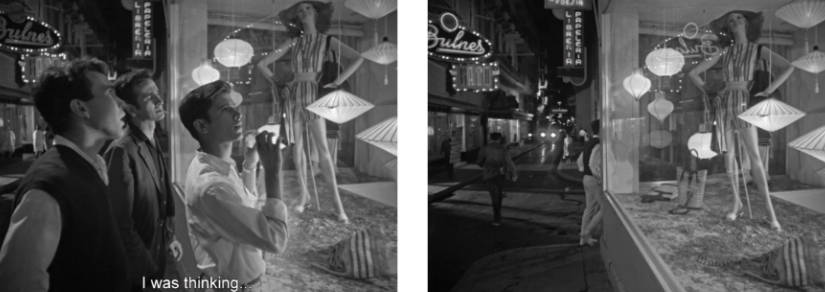

Figure 4. Enrique and Co. walk away from store

After leaving the drive-in theater, the students arrive in a fashion district. The low-key lighting and long shot direct the viewerʼs gaze to the surrounding environment with glamorous stores covering the skies. Against the dark night, the characters are illuminated by the display window lights, as if enamored by capitalism itself (see Fig. 3). The lighting style creates a stark contrast of light and dark, effectively dividing the scene into two and drawing attention to the brightly lit storefront display. In contrast, the space outside remains dark, affirming the artificiality of an idealized lifestyle that does not reflect the harsh conditions experienced by the masses. As such, capitalism is glamourized, while the characters are left in the dark, physically separated by a glass panel and looking longingly at what they cannot obtain—wealth. With Havanaʼs commercialization as a tourist destination in the early 20th century, becoming something of the Las Vegas of the Caribbean by the 1950s, these stores were likely geared toward foreign (mostly American) tourists (Figueras). The wealth generated in these fashion districts is not in the hands of the Cuban people, but in the hands of capitalists and corporations. As the characters walk off-screen, the camera remains fixed in position, creating a long shot that showcases the characters in relation to their surroundings (see Fig. 4). It also functions as an establishing shot that lets the audience fully take in the setting. The long shot enlarges the scale of the buildings, while the characters appear smaller and smaller as they move out of frame. The mannequin in the display window and the shop signages—products representative of capitalism itself—tower over the characters, making the alleyway seem almost claustrophobic. In juxtaposing the characters with their environment, the film visually underscores how the Cuban people appear insignificant and powerless against the capitalist machine. This contrast emphasizes that while wealth may seem beneficial to the economy, it remains out of reach for regular Cuban people.

Figure 6. U.S. Navy sailors approach Gloria

The deep focus technique accentuates the imposing stature of the U.S. Navy sailors and the disturbance they bring to an otherwise peaceful, quiet night. Though never explicitly identified as American sailors, their uniforms and patriotic singing make their identity clear. As they walk down the street, the foreground, middle ground, and background are all in focus (see Fig. 5). The use of deep focus here allows the viewer to easily track their movement—emerging from around the corner, quickly spreading out and occupying the entire street, and eventually dominating the frame (see Fig. 6). This staging calls upon the “ugly American” stereotype: loud and obnoxious, someone who imposes themselves upon a new space theyʼve just entered. The lack of ambient sound in this scene further amplifies their intrusion. The sailorsʼ disruption of peace, both physically and auditorily with their loud singing, serves as an allegory for American military presence in pre-revolution Cuba; it is a foreign occupation that is disruptive and overall unwelcome. Given that the film is partially funded by the Soviet government and directed by a Soviet filmmaker, this portrayal is hardly surprising, as it reflects the political rivalry between the two nations. After all, it is only logical that the Soviet government would want to frame its archenemy as detestable and arrogant people. When viewed in this light, this scene takes on a binary good versus evil political undertone.

The portrayal of these sailors as morally corrupt individuals intensifies as they proceed to harass a local woman all the while singing a cheery patriotic tune. The use of contrapuntal music establishes an ironic juxtaposition between the sailorsʼ self-proclaimed heroism and their repulsive actions.3 The sailorsʼ singing can be heard before they appear on screen. They sing of hailing from “the greatest country here on Earth” and being “the heroes of old Uncle Sam.” Initially, the song functions as a non-diegetic sound, seemingly part of the filmʼs background music. This creates an ominous atmosphere, evoking the imagery of a predator stalking its prey and announcing its overpowering presence. As the sailors come into view, the music seamlessly transitions to diegetic sound, revealing them as its source. This shift characterizes the perpetrators as people who genuinely believe in their own righteousness, which makes their abhorrent behavior all the more chilling. As a parody of real American patriotic songs, the lyrics further heighten the irony. The lyrics are distributed so that as the sailors surround Gloria, moments before assaulting her, they chant the line “Here comes the Navy, hooray!” (see Fig. 7). The cheery, catchy tune contradicts the dark mood of the scene, amplifying the disturbing visuals on screen. The juxtaposition underscores the disturbing lack of self-awareness exhibited by the soldiers. These men, who are representative of their country, sing of their supposed virtuousness while they harass an innocent woman who just happens to be passing by. This contradiction mirrors the broader hypocrisy of American imperialism: how can a nation proclaim itself the greatest country in the world, when it is actively exploiting the land and people of Cuba? As such, this scene serves as an overt condemnation of American military imperialism, with the filmmakers unmistakably positioning America as the enemy of Cuba.

Figure 9. U.S. Navy sailors chase after Gloria

As the sailors chase Gloria down the street, the use of shot-reverse shots and low camera angle evokes a predator-and-prey dynamic between the two parties, representative of the power imbalance between America and Cuba. The scene switches between a close-up shot of Gloria and one of the sailors, simulating her view as she frantically looks around. The rapid cuts between her panicked expression and the sailors pursuing her heighten the tension, emphasizing the source of her distress. By keeping the camera running alongside Gloria, the viewer experiences her point of view, with frenzy movement exaggerating the direness of the situation. According to Latin American film researcher Amit Thakkar, the American characters in I am Cuba are portrayed as sexual predators while the female characters are reduced to “feeble” figures, with Gloria depicted as “a rather pathetic admirer” of Enrique who comes to save her. This depiction extends to this scene, where the cameraʼs positioning exemplifies her lack of dialogue and thus individual agency. The low-angle shot forces the audience to look up at both her and the sailors, reinforcing her powerlessness and evoking sympathy. Through this visual dynamic, Gloria is cast as the helpless victim, while the sailors are undisputedly villains—drawing on the portrayal of Cuba falling prey to American imperialism.

The symbolic framing and blocking of Gloria standing behind a display window visually equates her with the items for sale, reinforcing the filmʼs theme of the commodification of Cuba.4 As the camera follows Gloriaʼs movement, shifting from the center of the frame to around the corner peeking behind the glass panel, she becomes another commodity on display. The framing traps her behind glass, denoting her objectification and lack of agency. This scene can be read as an extension of the filmʼs opening shot, which features bikini-clad Cuban women showing off their bodies and advertising their swimwear to tourists. As cultural historian of the Soviet Union Anne E. Gorsuch explains, such depiction of a “steamy, sexual [pre-revolutionary] Cuba” catered to “the tourist experience” is typical of Soviet cinematography. Gloriaʼs portrayal in this scene falls into this category. She is first treated as an object of desire by the American sailors, then physically enclosed in a storefront display, serving as an allegory for Cuba itself—trapped between the forces of tourism, capitalism, and foreign exploitation. Desirable, yet ultimately powerless.

As is typical of a propaganda film, the main agenda of I Am Cuba is obvious: Cuba is a victim in need of a savior—specifically, revolutionaries who stem from a grassroots movement and are willing to lay down their lives for the cause. The film is careful to show that while Cuba is a victim, it is not weak. This is evident in the scene where the revolutionaries bomb a theater, suggesting that the only way to return power to the hands of the people is by force. The insinuation is that violence is a necessary step toward liberation, and rebuilding a nation may begin with an execution (metaphorical or literal, depending on the circumstances). With its overtly stereotypical and almost comically on-the-nose depictions of American soldiers and businessmen, the film is rich in anti-American sentiment. Every chance it gets, it does not shy away from reminding the viewer that the United States is the antagonist. It is a stronger enemy; a personal enemy of Cuba. Against this formidable villain stands the true hero: the revolutionaries who told Cuba to rise up and bring this oppressive force down to its knees.

Footnotes

1 The incorporation of real-life footage adds a sense of realism to the events depicted in the film.

2 The bombs used were Molotov cocktails, an improvised weapon used in civil protest and riots oftentimes against a corrupt government.

3 Contrapuntal music is a type of contrapuntal sound, which occurs when two different meanings are implied by the sound or when the sound contrasts strongly with the mood, tone, or visuals of the scene (Corrigan and White).

4 Blocking is the physical arrangement and movement of characters in a scene, in relation to other characters or objects (Corrigan and White).

Annotated Bibliography

Primary Source

I am Cuba. Directed by Mikhail Kalatozov. Milestone Films, 1964.

I am Cuba is a political drama, propaganda, and anthology film consisting of four shorter films (called “vignettes”) known for its use of innovative film techniques. It follows the lives of the Cuban people in pre-revolutionary Cuba. In the first vignette, Maria works as a prostitute unbeknownst to her lover. Second, Pedro learns that his farmland is being sold to an American company. Third, Enrique and his fellow student revolutionaries clash with the police. Finally, Mariano joins the revolutionary forces after his family is bombed by the government. The film is a co-production between the Soviet Union and Cuba, funded by the Soviet and post-revolution Cuban governments with the intention to promote global socialism and communism. Considering that the film is financed by the Soviet and Cuban governments, the filmmakers may be inclined to portray the Cuban Revolution in a romanticized or positive light. I examine how the film offers a critique of pre-communist Cuba. I am also interested in analyzing how the bias of the filmmaker is shown in the final product, namely the anti-American sentiment fueled by the animosity between the Soviet Union/Cuba and the United States.

Secondary Sources

Gorsuch, Anne E. “‘Cuba, My Loveʼ: The Romance of Revolutionary Cuba in the Soviet Sixties.” The American Historical Review, vol. 120, no. 2, 2015, pp. 497–526. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43696680.

In this article, cultural historian Anne E. Gorsuch examines the factors that contributed to the exoticization and romanticization of Cuba in the Soviet Union, particularly during the 1960s. Gorsuch remarks that Soviet affinity for revolutionary Cuba partially stems from the Russian Revolution and Civil War, which share many parallels with the Cuban Revolution, including freeing oppressed people from a dictatorship and evoking youthful participation. The Soviet Unionʼs repression of sexuality is identified as the main cause of Cubaʼs exoticization, as the island nation provides an outlet for socialist eroticism deemed appropriate by the state. The article discusses a variety of artifacts that are Soviet depictions of Cuba, including posters, photographs, and films. The focus on the sixties, the same period in which I Am Cuba was filmed, helped me gauge the attitude that the Soviet director and cinematographer held toward Cuba and assess how those biases may have been reflected in certain scenes. I used the article to support my analysis that one of the major themes of the vignette is the sensual depiction and commodification of women in pre-revolutionary Cuba.

Oukaderova, Lida. “I am Cuba and the Space of Revolution.” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary

Journal, vol. 44 no. 2,

2014, p. 4-21. Project MUSE, https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/flm.2014.a562886.

In this article, Lida Oukaderova, a specialist in the history of European and Russian cinema, examines the spatial tropes or movement through space in the film I Am Cuba. Oukaderova argues that through camerawork that influences charactersʼ decisions and changes how the viewer engages with the film, space itself is personified to embody the revolutionary spirit of the Cuban Revolution. Oukaderova brings in much additional historical information to contextualize certain scenes. Her breakdown of the drive-in theater scene helped me gain a better understanding of the significance of the location being a drive-in rather than a regular theater. It inspired me to make the argument that the theater is representative of American cultural imperialism, and incorporate it into my thesis. I used this article as a jumping point to bring in a new reading of the bombing as a disruption to the physical space, which is representative of the status quo.

Thakkar, Amit. “Who Is Cuba?: Dispersed Protagonism and Heteroglossia in Soy Cuba/I Am Cuba.”

Framework: The Journal of

Cinema and Media, vol. 55 no. 1, 2014, p. 83-101. Project MUSE,

https://dx.doi.org/10.13110/framework.55.1.0083.

In this article, Latin American film researcher Amit Thakkar argues that I Am Cubaʼs championing of the Cuban Revolution cause and the portrayal of its protagonists is a direct response to Hollywood cinema. Thakkar emphasizes the unitary language of Hollywood, where there exists a clear single individual protagonist or hero. In contrast, I Am Cuba practices dispersed protagonism, where the weight is distributed across the protagonists equally. The protagonists function as a whole, representative of a greater cause. Thakkar identifies Mikhail Bakhtinʼs literary theory of heteroglossia as the basis of his argument but does not provide a clear definition of the theory. I had noticed that the first meeting of Gloria and Enrique plays into the damsel in distress trope, and this article offered insight into how this may be performing or conforming to gender stereotypes. From there, I was able to connect Gloriaʼs lack of individual agency in this scene to how it represented the dynamic between Cuba and the United States.

Works Cited

Corrigan, Timothy, and Patricia White. The Film Experience: An Introduction. 6th ed, Macmillan Learning, 2020.

Gorsuch, Anne E. “'Cuba, My Loveʼ: The Romance of Revolutionary Cuba in the Soviet Sixties.” The American Historical Review, vol. 120, no. 2, 2015, pp. 497-526. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43696680.

I am Cuba. Directed by Mikhail Kalatozov. Milestone Films, 1964.

Miguel Alejandro Figueras. “International Tourism and the Formation of Productive Clusters in the Cuban Economy.” 1 Sept. 2001. https://web.archive.org/web/20040805035546/http://www.world-tourism.org/quality/E/docs/trade/cubacontrib.pdf.

Oukaderova, Lida. “I am Cuba and the Space of Revolution.” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 44 no. 2, 2014, p. 4-21. Project MUSE, https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/flm.2014.a562886.

Savela, Edward. “The United Statesʼ Role in Making Cuba Communist.” Vulcan Historical Review: vol. 16, article 4, 2012.

Thakkar, Amit. “Who Is Cuba?: Dispersed Protagonism and Heteroglossia in Soy Cuba/I Am Cuba.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, vol. 55 no. 1, 2014, p. 83-101. Project MUSE, https://dx.doi.org/10.13110/framework.55.1.0083.